Words by Chris Lee

Sept. 26, 2016

In 2014, a widely shared youtube video recorded a dispute between tech bros in San Francisco’s Mission District and local youth over the use of a public soccer field.[1] The tech bros insisted on their entitlement to use the field exclusively for 1-hour by presenting a San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department permit that for the cost $27 would reinforce their claim. The permit’s legitimacy was contested by the youth who countered that in the local custom, the field had never been “booked,” and thus could not be “booked” now simply because one possessed a permit. The tech bros’ incredulity that the document they held—in this case, a banal graphic design artifact that facilitates the governance of space—did not possess the legitimacy to back their claim is this text’s object of inquiry.

I would like to use this incident to open a consideration of the extent to which graphic design has been mobilized as an instrument of statemaking, and via colonization, impose a normative universalization of its logic. The park permit, as a graphic artifact, with its attendant references to maps and legislation, and to the extent that it enables a presumption of the legitimacy of its issuing agency and the claims of its holders, supplies a lens through which the persistence of colonial dispossession can be apprehended in its most banal forms, and hopefully, can inversely contribute to articulating possibilities of subversion.

The independent journal of landscape architecture and political economy, Scapegoat, [2] opens its first issue with the assertion that private property is to be understood as the “literal foundation” of architecture and landscape architecture practice, where each project begins with a site that is “already drawn.” [3] This paper attempts to outline a similarly fundamental insight with regards to graphic design. It focuses on typography, mapping, and the writing of legislation—each representing what Bruno Latour might consider “deflated” forms, or what Lisa Gitelman might regard as “genres” of graphic design—as primary constituents of an entanglement between graphic design and state power. In other words, graphic design is understood here as a practice where typography, mapping and legislation, not only make design’s entanglement with power particularly evident, but to the extent that they are embodied by standards, are precisely constitutive of their own status as faits accompli, or “already drawn.”

This text is an initial foray into probing the extent to which is “already drawn,” or what I will refer to throughout as standards and conventions (that which has moved beyond mutability or contestation), constitute the presumptive site on which graphic design practice is built to facilitate “…determined [hierarchical]…relations as [ostensibly] open aesthetic possibilities,”[4] and to propose that standards and conventions be understood indeed as politically constituted and thus available as sites of contestation through design practice. The kind of question this begs then is how? For instance, if maps, rather than “represent[ing] geographies or ideas… effect their actualization,” [5] what is it that sustains this effect? What gives a document like the park permit, or a colonial map for that matter, its power to define, to make immutable fact, establish convention, and to make incredulous or violent those who encounter an “illiteracy” of its claims?

What is at stake in the recognition of the contingency—that is, the political dimension—of writing, mapping and law, stabilized by their conventionality, is the affirmation of testimony and claims that fall outside the statist/colonial forms of legitimacy these underwrite. This project is partly inspired by the Dene scholar Glenn Coulthard’s critical work on Indigenous land claims struggles that assert an ontology of land as cultural and reciprocal (what he terms “grounded normativity”) [6], as opposed to commercial and commodifiable (what I’ll call “settler normativity”). Land claims politics in Canada has been characterized by an irreconcilable epistemological agonism where the Canadian state’s legal gaze understands land solely as property/commodity, and the more radical elements of the Indigenous struggle reject this and instead see it as cultural. The Indigenous argument for cultural rights (which the Canadian state insists is distinct from political rights) then figures an ontological understanding of the land as “…a field of ‘relationships of things to each other,’” [7] as opposed to land as objective commodity in the form of private property (valorized as such through colonial dispossession).

The premise that I am attempting to establish in what follows is a narrative of graphic design functioning as an instrument of dispossession and colonization. [8] What I posit is that the graphic genres mentioned above (typography, mapping, legislation) mobilized by the settler state to validate its claims and render its land legible as property, privilege the empirical while holding a conceit of objectivity (precisely by virtue of their status as visible, being outside any individual subject), simultaneously making illegible and therefore “illegal” any form of “grounded normativity.” My hope is that doing so will help build a discursive ground which puts into relief graphic design’s coloniality, while scrutinizing its recesses to address problems of colonial legitimacy.

Typography and Myth

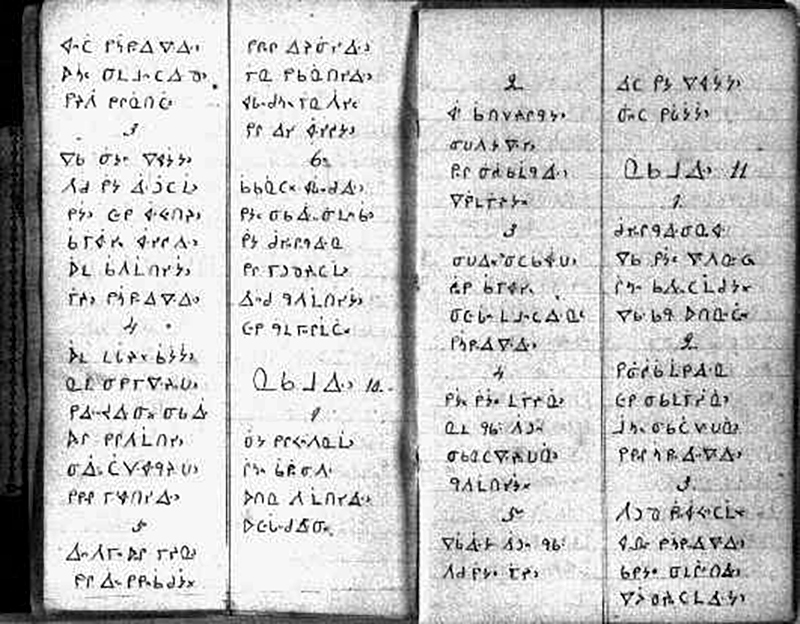

I begin with the contention that the Cree syllabary was ostensibly the first typeface to ever be designed within the settler-state now known as Canada.[9] However, I am less interested in the merit that it was the first, and rather seek to address the notion that it was designed. Benedict Anderson’s account of print-capitalism casts typography as an actant that compelled the standardization of language and the imagination of national communities.[10] Furthermore, following Anderson’s accounting of the role that myths play in the production of a shared origin story that underwrites nationalistic sentiment, I contend that it is precisely typographic history, particularly in the context of national/colonial myth-making, that casts typography and printing as a modernizing/civilizing agent.

Winona Stevenson, an Indigenous Studies scholar at the University of Saskatoon, recounts the story of Calling Badger—a Wood Cree elder who received the Cree writing system (which has now been adapted for use in numerous Indigenous languages).

“On his way to a sacred society meeting one evening Calling Badger and two singers came upon a bright light and all three fell to the ground. Out of the light came a voice speaking Calling Badger’s name. Soon after, Calling Badger fell ill and the people heard he had passed away. During his wake three days later, while preparing to roll him in buffalo robes for the funeral, the people discovered that his body was not stiff like a dead person’s body should be. Against all customs and tradition the people agreed to the widow’s request to let the body sit one more night. The next day Calling Badger’s body was still not stiff so the old people began rubbing his back and chest. Soon his eyes opened and he told the people he had gone to the Fourth World, the spirit world, and there the spirits taught him many things. Calling Badger told the people of the things he was shown that prophesized events in the future, then he pulled out some pieces of birch bark with symbols on them. These symbols, he told the people were to be used to write down the spirit languages, and for the Cree people to use to communicate among themselves.”

This story contradicts the colonial history of Cree script, which attributes its invention in 1840 to English linguist and missionary James Evans, who melted down the clasps of his tea chest to create type slugs and printed translations of religious texts and hymns. One story, borne out by documentary evidence, attesting to the ingenuity and benefit of the European settler, is considered plausible and credible—fact. Evans’ printing specimens are preserved and available to researchers; there are other sources that corroborate his story; it is possible to draw formal and conceptual continuity between the Cree syllabary and Evans’ knowledge of Devanagari and Pitman shorthand.

On the other hand, the oral history recalled by Stevenson, attributes the creation of the writing system to the spirit world and its transmission through Calling Badger leaves no hard evidence, no “mobile immutable”[11] that can be traced back and verified, nothing to scan and reprint or upload—no original document. Outside of an epistemological framework underwritten by empirical observation, such claims are invalid and reminiscent of fraud, deceit, belief, blind faith, abuse, dangerous irrationality. It seems hardly necessary to go beyond my own problematic reading of the story as evidence to support my presumption that the Indigenous story would often, at best, be trivialized with patronizing curiosity and at worst dismissed as primitive mythology.

I propose that the gap between these two stories could be understood (in very general terms) as the gap between a European colonial epistemology and an Indigenous one. To illustrate this, I point to the conceptual consistency between the contentious typographic history described above and the Indigenous land claims struggle in Canada. Where a settler-normative epistemology is imbricated with a statist ontology of land as commodity/property, the phenomenon of the typographic object is attributable to a legal individual’s intellectual authorship. This would be counterposed to an Indigenous “grounded normativity” which is imbricated with an ontology of land as reciprocal relationship, a kind of medium that is immune to private ownership. This is to suggest that the ontological status of the script differs radically according to the possibility of producing empirical evidence. The document—a graphic artifact—thus performs an evidentiary function [12] and affords the narrative for which it does so the distinction of being historical or, “already drawn.”

Perhaps one way to challenge the diminishing of that which leaks outside of the indemnity of colonial epistemology would be a deliberate performance of illiteracy—a deflection of its insistence on the visible, empirical and privileging of objectivity as the sole guarantee of validity and legitimacy. This need not be a wholesale rejection of empirical validation, but rather a strategic deflection of empiricism as an instrument of colonial dispossession, both spatial and cultural. To claim then that the script was “designed” (with an author as its source) and not “received” (from the spirit world) is the reinscription of a settler-normative form of historical validation based on the availability of documentary evidence (the “already-drawn”) towards the production of national settler mythology.

Though the actual story may be somewhere in between the Evans and the Calling Badger story (for example, that the writing system had been in use when the Cree encountered the missionaries, but that the missionaries took credit for its invention), it is more interesting to consider the Evans story as an instrument of national myth-making. The official rhetoric of Canadian state multiculturalism, for instance, ought to be understood as being entangled with the legitimization of the settler-multicultural colonial state, in the sense that it casts as unproblematic, and certainly beneficial, the presence of European settlers on Turtle Island.[13] If that were acknowledged, then what we’re dealing with either way are different mythologies. What could then be ventured is that a deliberate neglect of documentary evidence and empiricism—or what Walter Mignolo might call a form of “epistemic disobedience”—is a politically valid deflection of a persistent settler-normativity.

Legibility and Landscape

The premise of the section that follows is that the notion of legibility—as a concern both in graphic design and statecraft—brings into the spectrum of concerns, agendas and forms that are not typically associated with graphic design, mapping and legislation, as politically consequential modes of practice. What is sought through this exercise is an understanding of the mobilization of graphic artifacts in producing normative standards rooted in modernist, bourgeois liberalism as the basis of (settler) legitimacy.

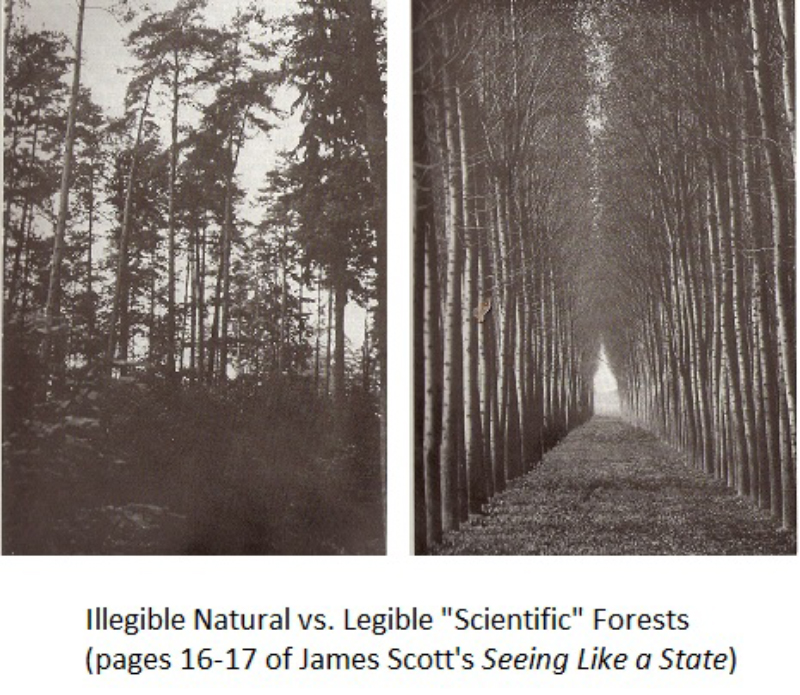

The anthropologist James C. Scott describes the development of the scientific forest as a prime example of the way landscape is designed in order to make it legible. Mid-19th-century Prussian foresters, seeking to manage unregulated and unsustainable forestry practices sought to design a landscape that would facilitate the rational management of lumber harvests. The foresters desired to form the land in a way that could be managed from the overview perspective of a chart inscribed with numerical representations and arranged with graphical logic. The illegible wild forest was thus transformed to reflect the ordered legibility of the chart in a turn to what I call “the banality of ‘excel.’”[14] In the short-term this enabled a more accountable means of managing lumber harvests, and would ostensibly create a more sustainable supply. However, the long-term result was the foresters realizing that their designed landscapes were not in fact as sustainable as they had anticipated because the biological/nutritional deficiency of simplified ecosystems made the forests more vulnerable to disease and extreme weather. What they had failed to account for were precisely those things that were illegible to a gaze that was conditioned by commerce and economistic calculation—the dynamic inter-relationality of insect life, rodents, ground-plants, animal droppings, and so on, that were constitutive of the landscape’s vitality.

Such myopia characterizes the Canadian state’s illiteracy when it comes to an understanding of land that mediates “forms of life” and their attendant cultures, illegible to a statist gaze. Rather the Canadian state prefers to separate land and culture in a way that allows for the recognition of Indigenous “culture” on the condition of a consensual understanding of land as property. Quoting Paul Nadasdy, Coulthard points out that “…‘to engage in the process of negotiating a land-claim agreement, First Nations people must translate their complex reciprocal relationship with the land into the equally complex but very different language of ‘property.’” [15]

Property is something that landscape architect and theorist James Corner would characterize as a “…phenomena that can only achieve visibility through representation rather than through direct experience.”[16] The spectrum of what is made legible on the proverbial map of the Canadian state, makes recognizing Indigenous “land rights” claims mean little more than the right to buy and sell land in a market regulated by the state.

Standards and the “Already Written”

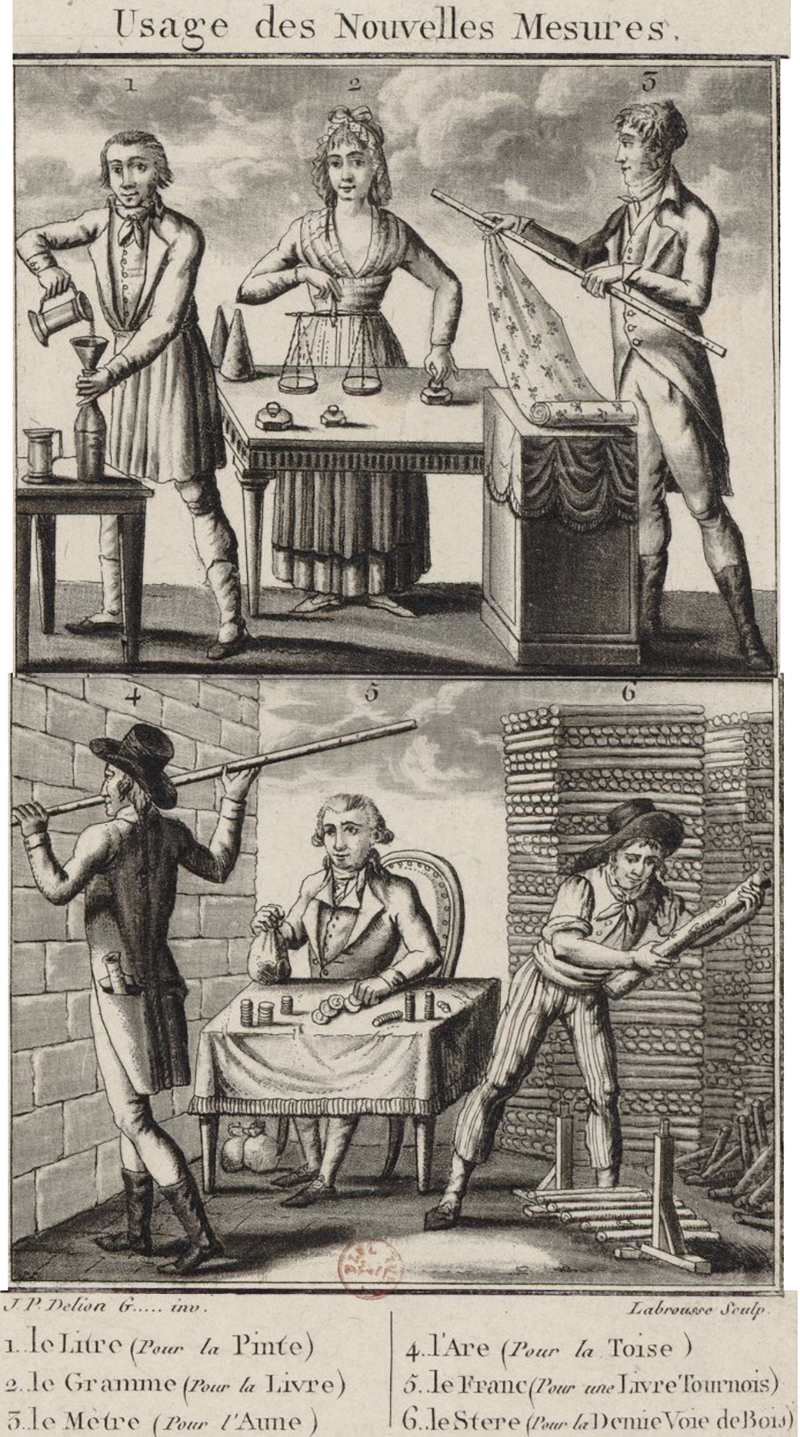

In seeking the source of this colonial ontology of land-as-property and the coordinates by which it can be regulated, we can go again to James C. Scott who reminds us that one of the aims of the French Revolution was the establishment of “one king, one law, one weight and one measure.” It was declared that the Revolution had given the people the metre![17] A common grievance brought to the cahiers de dolénces (statement of grievances) was the arbitrariness of the standards used by local aristocrats and the clergy, that through customary arrangements, left subject populations vulnerable to economic abuse. Scott supplies examples of the various ways in which a landlord might abuse such customary feudal rental arrangements to dispossess their tenants of their production.

“The local lord might, for example, lend grain to peasants in smaller baskets and insist on repayment in larger baskets. He might surreptitiously or even boldly enlarge the size of the grain sacks accepted for milling (a monopoly of the domain lord) and reduce the size of the sacks used for measuring out flour; he might also collect feudal dues in larger baskets and pay wages in kind in smaller baskets. While the formal custom governing feudal dues and wages would thus remain intact (requiring, for example, the same number of sacks of wheat from the harvest of a given holding), the actual transaction might increasingly favor the lord.”[18]

Here the politics of standards and measurement are at play. For Scott, “every act of measurement was an act marked by the play of power relations.” [19]

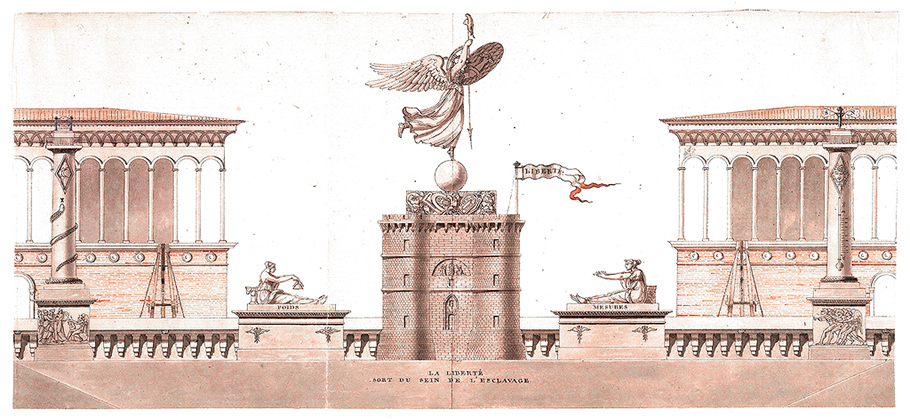

Proposed renovation of the Bastille Prison as a monument to the metric system.

Instructional graphic for usage of the new metric standards.

In the early years of the new Republic, a proposal was made by “revolutionary architects”[20] for a monument to be built on the site of the former Bastille prison that would commemorate (and be immutably set in stone and metal) a new system of standardized weights and measures. While this was never actually built, the French Academy of Sciences was commissioned to devise a new rational system that would displace the traditional legal privileges of the aristocracy and clergy. These would eventually materialize as objects—the metre, for instance, was a stick that was, well, a metre, but whose length was to be determined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator. Other standardized units, like the kilogram, were derived tautologically from the volume of one-thousandth of a cubic meter of pure water. The public validity of these standards rested on the impersonal, empirical phenomena on which they were derived, and were thus held up as objective and immune to the traditional and arbitrary forms of adjudication and administration of the old local standards. They embodied a graphic foundation for legislation whose immutable metallic composition, esoteric and scientific rationalization stood in for the infallible authority of a state whose legitimacy would no longer need to rest on the monarch’s divine right to rule. This system of standards would become a universalized inheritance whose validity rested on a conceit of rational objectivity (and the state power to uphold that conceit). It was also part of a political commitment to the legislation and regulation of markets for a bourgeoisie now liberated from the relative inequities of the ancien régime.

Though the newly minted settler republic, the United States of America, would not adopt the metric system, the same political/ethical principles of a universal standard were applied to its landscape in the form of the Jeffersonian Grid (1785). The Jeffersonian Grid was essentially the partitioning of land into one square mile parcels. It represents a rationalization of the landscape, making it subject to the legal order (the legibility) of the state. Indeed the map functions as a visualization that figures land as property precisely through its graphic design(ation) as such. The (colonial) state ratifies this designation by virtue of its capacity to impose its definitions through force (legality). To illustrate, I digress only slightly. Take for instance the Water Protector who famously disarmed the armed security contractor/infiltrator at Standing Rock and is now being criminalized for “terrorizing” said infiltrator.[21] The way in which an armed infiltrator is figured as the victim by the courts is a testament to the metaphysical power of the state. The Jeffersonian Grid manifests the ideals of a bourgeois state and thus superimposes them as a graphic articulation of liberal universalist values on an otherwise contingent, variegated and plural landscape. The map then produces a kind of “Heisenberg effect” to the extent that the gaze of the state, made operational by its epistemological apparatus (mapping, legislation) valorize an ontological status of land-as-property while simultaneously rendering illegal (illegible) an ontology of land not as discrete object but as a medium through which reciprocal economic relationships are facilitated.

What was fought for in Europe as the basis of a value system, a set of standards (the “already drawn”) upon which the laws of a democratic republic could be built, would be violently imposed on Turtle Island (amongst other colonies) as “enlightened” and “civilized,” ontologizing land as legible commodity (governable, legal), regulated by a statist/colonial legal apparatus (courts, police, military, schools, etc.) and rendering illegible (ungovernable, illegal) local/indigenous forms of governance and exchange. The inherited consensus of rational and irreducible standards obscure the possibility of “thick” potentials of plural and indeed, antagonistic definitions of land, myth and law that could privilege Indigenous ones and trivialize colonial ones. Perhaps a project of decolonizing graphic design calls for, as the youth in San Francisco demonstrated, strategic and deliberate performances of illiteracy—or to use Mignolo’s more deliberate and energetic term, a carrying out of “epistemic disobedience.” As a corollary, one task for decolonized design may be the pluralization and invention of forms and standards that reinforce epistemologies of land that require different literacies that deflect the colonial one, and for these forms of literacy to saturate processes of social reproduction that are countervalent to the colonial ones. What this looks like for those registers of graphic design that have been entangled with state power—typography, mapping and legislation—how much of its current disciplinary boundary ought to be retained, abandoned or more explicitly and critically engaged in order to mutate the conventional scope of the discipline, how much it needs to shift its concerns and modes of practice to consider this possibility, is a question for much further inquiry.

Notes

- [1] “Mission Playground is Not For Sale,” MissionCreekVideo, accessed September 26, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awPVY1DcupE

- [2] I was Scapegoat’s designer from issues 00 to 05, and a co-editor from issues 01 to 05.

- [3] Scapegoat Collective, “Editorial Note,” Scapegoat 00: Property (2010): 1.

- [4] Scapegoat Collective, “Editorial Note,” 1.

- [5] James Corner, “The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention,” in The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation, eds. Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, Chris Perkins, (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011), 255.

- [6] Glenn Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 13

- [7] Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks, 61.

- [8] Glenn Coulthard focuses on the dispossession of land through colonization over proletarianization as the foundation of a decolonial and anti-capitalist political subjectivity.

- [9] There is also the claim that Canada’s first typeface was Cartier, named after the French explorer Jacques Cartier, and designed and released by Carl Dair in 1967. Cartier was commissioned on the occasion of Canada’s centennary celebrations and would be used to typeset the Canadian Charter of Rights.

- [10] See chapter 3 of Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, (London: Verso, 2006).

- [11] See Bruno Latour’s “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together,” in Knowledge and Society Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present vol. 6, ed. H. Kuklick, (Greenwich: Jai Press, 1986), 1–40.

- [12] See Lisa Gitelman’s Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

- [13] See Richard Day’s “Multiculturalism and the History of Canadian Diversity,” (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000). Day develops the argument that the Canadian imaginary of an harmonious multicultural nationhood obfuscates its status as settler multicultural nation state.

- [14] As in Microsoft Excel. I know this is anachronistic, but I couldn’t resist the joke.

- [15] Coulthard, 78

- [16] James Corner, “The Agency of Mapping,” 229.

- [17] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 32.

- [18] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, 28.

- [19] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, 27.

- [20] “FOR LIBERTY, EQUALITY, AND THE METRIC SYSTEM,” Cabelle Ahn, accessed September 26, 2016, http://www.cooperhewitt.org/2014/09/04/for-liberty-equality-and-the-metric-system/

- [21] “Arrest Warrant Issued For DAPL Protest Hero,” The Young Turks, accessed September 26, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fApLi5DJ6gM

About the Author

Chris Lee is a graphic designer and educator based Buffalo, NY. He is a graduate of OCADU (Toronto) and the Sandberg Instituut (Amsterdam), and has worked for The Walrus Magazine, Metahaven and Bruce Mau Design. Through his research practice, Lee explores graphic design’s entanglement with power, standards and legitimacy. He has contributed projects and writing to the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, The Copyist, Graphic, Volume, and Counter Signals and has facilitated workshops in art institutions in the US, Scotland, the Netherlands and Croatia. Currently, Chris is an Assistant Professor at the University at Buffalo SUNY, a member of the programming committee of Gendai Gallery, a design research fellow at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam (2017/18) and formerly with the editorial board of the journal Scapegoat: Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy. cairolexicon.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.